Collaborative commissioning: Three things we’ve learned along the way

School exclusion is not simply an educational matter, but a symptom of complex issues that a young person faces in a highly fragmented system.

Our 2020 report, Who’s at risk of exclusion?, revealed that a small cohort of children and young people, representing just 15% of pupils, account for almost 60% of multiple fixed term exclusions. It is this cliff-edge group who may not meet any singular threshold for additional support and are at higher risk of exclusion since the pandemic. February 2022 marked a significant milestone in our mission to help children and young people at risk of school exclusion, through our Maximising Access to Education programme. The appointment of Power2 as our delivery partner, in Cheshire West and Chester, was the culmination of a joint commissioning process that embraced the co-produced spirit of the programme from the outset.

For us, collaborative commissioning was vital to enable a decision-making process that captured the voices of children, their families, service providers, schools and the council in the local area to make the process as equitable as possible. This was our first venture into collaborative commissioning, and we experienced a steep learning curve as we sought to include the voice of those impacted by school exclusion at the heart of the process to get the best possible outcome. We’ve summarised the key learnings from our experience and top tips that could help you on your own journey.

Lesson 1: Co-production isn’t one-size-fits-all

We wanted a delivery partner that would meet the needs of those who would either use or work within the model. This meant that we first had to seek the views of those who would be involved. Yet we questioned the limiting nature of full co-production at every stage of the process and adopted a more nuanced approach. For example, at the beginning of the process, we held a market-warming event and invited local service providers and prospective applicants to share key insights on what good practice in commissioning looks like. We incorporated their feedback directly into the process. Conversely, it was not appropriate to ask children and young people to read through applications and sit on the decision-making panel. Instead, through surveys and informal discussions, we established what was important to them when receiving support from a trusted adult, which informed our final decision.

Top tip: Consider where taking a full co-productive approach does and doesn’t add most value. Various degrees of co-production are better suited at certain stages of a commissioning process and with different stakeholders. There can be a gold standard in therapeutic interviews, and a different gold standard for online surveys. The important point is to include these voices to inform the decision to avoid a tokenistic approach.

Lesson 2: Collaborative commissioning takes time

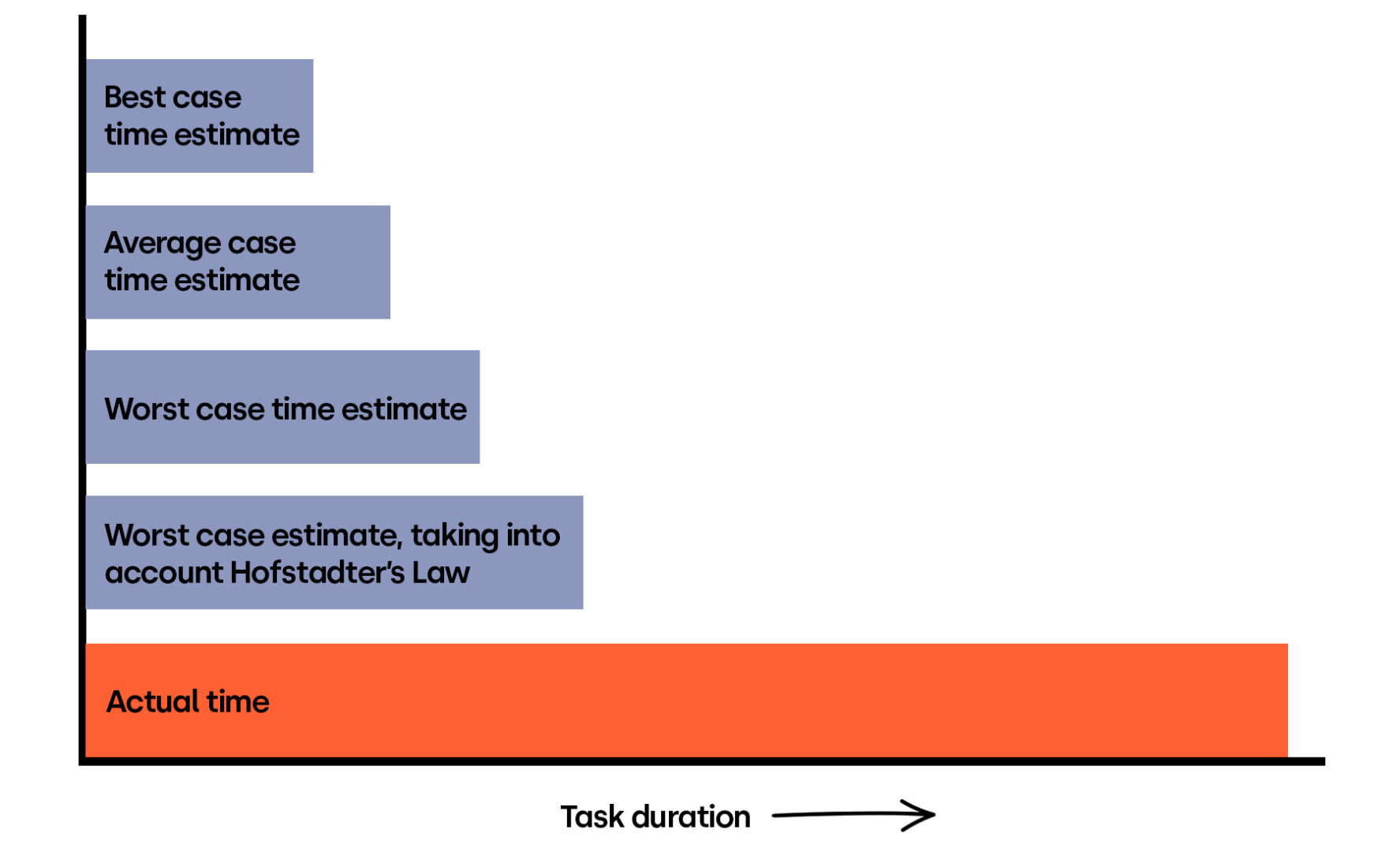

At every stage of the commissioning process, we found ourselves working close to each deadline, wishing we had more time than initially allocated. As Hofstadter’s Law states, it always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter’s Law.

What we noticed was that listening to and taking on board the voices of a wide group of stakeholders — children, young people, their families, schools, service providers and the council – simply takes time. Competing priorities, internal procedures and the unpredictable knock-on effects of Covid meant that sometimes we were waiting on feedback necessary to progress to the next key phase.

Top tip: This is not to say that an initial timeline should be wildly inflated. Instead, factor in that there could be delays that are out of your control and create a plan to mitigate delays on the overall project delivery. Provide key panellists with relevant information from the outset and give ample time for them to digest the materials and fill in numeric scores in advance of a wider panel discussion.

Lesson 3: Be flexible

In seeking the views of the community, we quickly learnt we can’t have the same expectations of everyone. Some members had a lot of time to give, others had demanding responsibilities elsewhere. To make sure we listened to all voices, not just those who are most available, we created an Expert Advisory Panel as separate to the decision-making panel. The expert advisers consisted of education professionals and local authority staff who we considered vital in contributing to the final decision, but had less time to offer.

Top tip: Ask key stakeholders ho w much time and resource they are willing to offer in advance of the process. Be mindful that often, partners in schools and local authorities have a lot on their plates and are completing such additional work on a side-of-desk basis. Make sure it fits around their existing responsibilities and be prepared to flex the deadlines, where possible.

Key takeaways

The joint commissioning process was both illuminating and humbling. We were ambitious in our goal to seek the input of key groups but were forced to acknowledge that it takes time and is not always appropriate to engage in full co-production throughout the process. A collaborative commissioning process is a worthwhile endeavour but be mindful that there aren’t too many cooks at the expense of risking project delivery.

We are excited about the potential of this work to be transformative through being informed by and directly accountable to children and young people. We are committed to our partnerships and to taking a local systems perspective to support earlier intervention for children and young people most at risk of exclusion.

If you’re interested in our work or would like to share any thoughts, we’d love to hear from you. Get in touch with us at SFeducation@socialfinance.org.uk.

Thanks to Matt Croston for his input and reviewing on this piece.